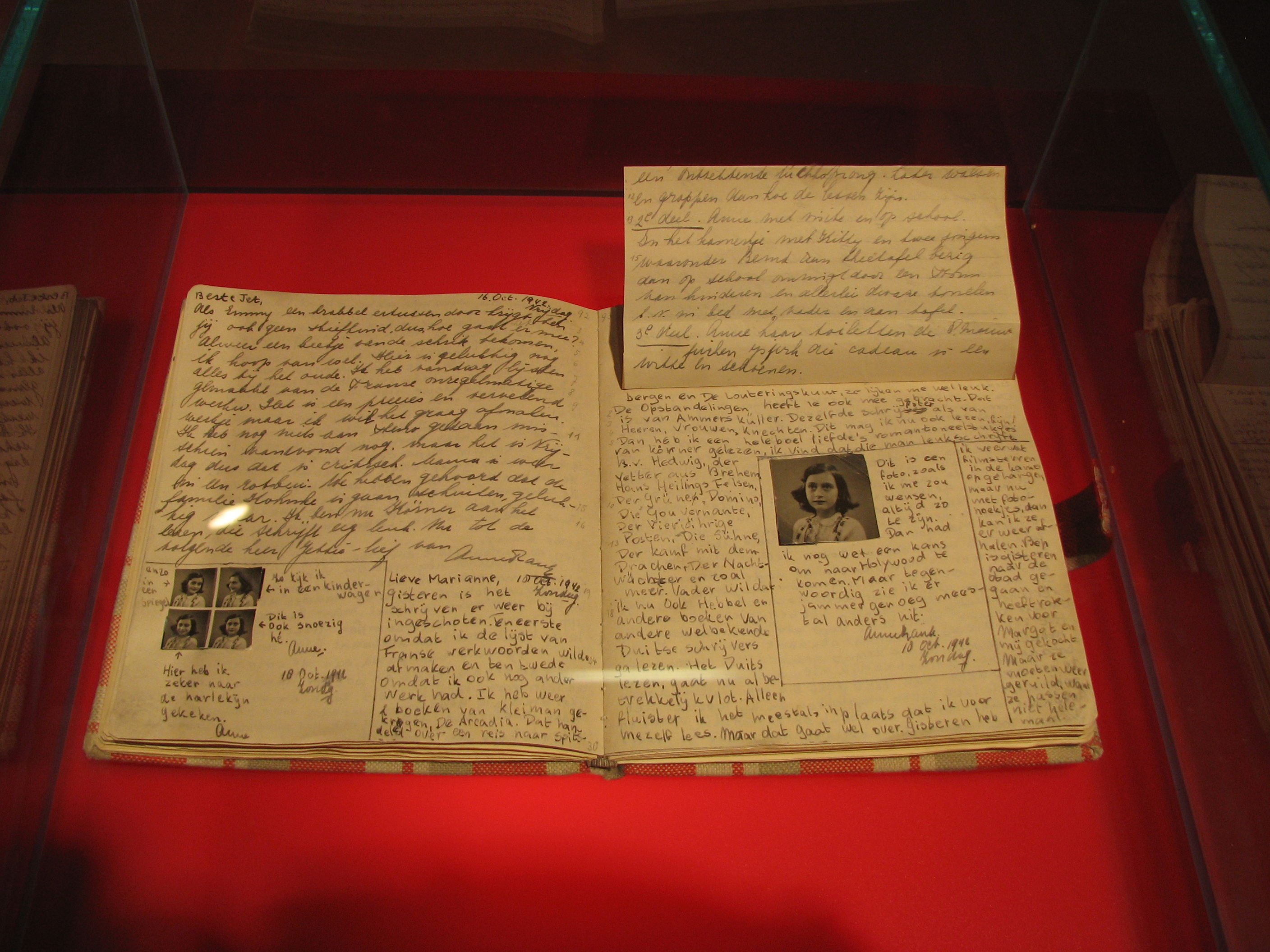

It is beyond dispute that Anne Frank’s diary is of great historical value. A recent Dutch court decision confirms this, in a case that perfectly illustrates the tension between freedom of scientific research and the enforcement of copyright. On the 23rd of December 2015, the District Court of Amsterdam handed down its ruling in a case that concerned the making of reproductions of Anne Frank’s diary for scientific purposes. The case was brought by the Swiss Anne Frank Fonds, owner of the copyrights in Anne Frank’s diary, against the Dutch Anne Frank Stichting and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW).

There has been a lot of fuss about the (extended) copyright in the diary recently, but I will not enter into that discussion here, save to explain that in the underlying case it was established that the copyright in important parts of Anne Frank’s works continues after 1 January 2016. My focus is instead on the fundamental right of freedom of scientific research and what it can contribute to research using text and data mining (TDM) techniques. I will briefly summarise the decision and discuss the consequences for TDM research.

Short summary of the case

Huygens ING (a research institute) created XML files from Anne Frank’s works in order to make a textual analysis of those works. These were based on facsimiles of her manuscripts and published diaries that were created with the authorisation of the Anne Frank Fonds (hereafter: Fonds). The files included meta data on, inter alia, annotations, changes in handwriting and deletions in the text. The Fonds did not authorise the creation of the XML files and claimed that they therefore infringed its copyrights in Anne Frank’s works.

The court found that the copyright exceptions invoked by the defendants did not apply to the creation of these files. However, the defendants also invoked their right of freedom of scientific research – as laid down by Article 13 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. The court recognised that a balance between fundamental rights is already assured in the establishment of a regulation. Nevertheless, it found that a judge must examine whether allowing a (copyright infringement) claim detracts too much from a fundamental right in a given case, if the parties’ arguments give rise to a reason to do so. The court underlined the principle of proportionality in assessing the balance between the enforcement of intellectual property rights and any fundamental right. It referred to a recent Dutch Supreme Court decision in the GeenStijl case (§5.2.5), where reference is made to the ECJ’s rulings in Scarlet v SABAM and UPC Telekabel Wien and the ECtHR’s decision in Ashby Donald v. France.

Turning to the circumstances of the present case, the court acknowledged the public interest of the research by Huygens ING, which was not contested by the Fonds. The court found that the fact that the parties to the proceedings had a disagreement on what approach to take emphasised the need for independent scientific research by multiple parties from different angles, shedding light on a variety of hypotheses. It also considered that the research conducted by Huygens ING would be impossible without the XML files, which are made exclusively for scientific research purposes. It was therefore up to the Fonds to substantiate why the enforcement of its copyrights outweighed the freedom of scientific research in this case, which it failed to do. The court added that copyright law does not protect the right to control which studies are carried out and which are not. Moreover, it followed from the fact that only a few researchers have access to only a few copies of Anne Frank’s diary that the infringement has no more than a minimal impact. Based on all the foregoing, the court concluded that the freedom of scientific research outweighed the enforcement of copyrights in this case.

Good news for TDM

So how does this affect the use of TDM in research? The good news for TDM research: this case shows the importance of the freedom of scientific research as a fundamental right, which may in certain circumstances prevail over the enforcement of copyrights (and intellectual property rights in general). To summarise the Dutch court, this is likely to be the case where infringements have minimal impact for the right holder, while the public interest is served and no other means are (reasonably?) available to achieve that (i.e. proportionality). I will apply these criteria to TDM research in general.

Minimal impact?

TDM activities only make reproductions for the purpose of extracting facts and ideas – which are as such not protected by copyright – from the works, without actually making available (parts of) the contents themselves. Normally, only researchers affiliated with the study will have (lawful!) access to the reproductions and often it is only a computer that will ‘read’ the contents. As in the court case, the reproductions may constitute copyright infringements, but it can be argued that the actual impact is minimal.

Public interest?

Whether TDM serves a public interest depends on the case, but this is more likely where scientific purposes are achieved.

Proportionality?

TDM research seeks to derive knowledge from large amounts of data that cannot (reasonably) be analysed by human minds alone. It may therefore be argued that there are no means to achieve that goal other than by using TDM techniques and that it therefore withstands the proportionality test.

Bad news for TDM

On the other hand, the court’s decision also means bad news for TDM scientists: the unauthorised reproductions of works – to which researchers have lawful access – are always deemed ‘infringements’ and any prevalence of fundamental rights has to be established on a case-by-case basis. Obviously, this does not provide any legal certainty for TDM researchers. It is therefore a task for the legislator to assure an appropriate balance, which is what the EU legislator has recently undertaken to do. The Commission intends to propose an exception by spring 2016 that “allow[s] public interest research organisations to carry out text and data mining of content they have lawful access to, with full legal certainty, for scientific research purposes”.

For TDM researchers, this may be a step forward. The EU copyright framework would finally have an exception specifically aimed at TDM. Moreover, the Commission intends to “make relevant exceptions mandatory”. This prevents cross-border differences to a certain extent, which is the problem with many of the current optional exceptions in the EU framework.

However, it is too early to rejoice for those involved in TDM research. It remains to be seen how strictly concepts such as ‘public interest research organisations’ will be interpreted. Does it only include publicly funded research institutes or are collaborations with privately funded entities also covered? This criterion plays a crucial role, considering that scientific research (with major public interest) does not necessarily rely merely on public money. Isn’t the ‘why’ of the making of a reproduction more relevant than the ‘who’? If reproductions are only made to let TDM software extract (unprotected) ideas and facts from the works, this is comparable to human beings reading books and using that knowledge to make new (and original) works. In that regard, I agree with Lucie Guibault that inspiration might be drawn from Article 5(3) of the Software Directive.

Conclusion

The court’s decision is definitely a win for academic freedom and TDM research. At the same time, it underlines that the EU legislator must take action to provide more legal certainty. Let’s hope the Commission’s upcoming proposal is able to achieve that.

(This post was originally published on Kluwer Copyright Blog.)